posthumous note 2/14/2026: i’m putting this up here just as a test of the blog and to also put this somewhere. this was written in part for my undergraduate thesis in spring of 2025. in many ways the arguments i make in this piece melt and warp under the current intensifying pressures of sex negativity. i would’ve also liked to do a little more legwork interrogating the fantasies of attractiveness, somewhat akin to the same questions of desire and psyche, but the main thrust of my thinking largely remains the same (dedramatizing the encounter with hardness and impossibility). how else should we describe our predicaments to reorient our sensoriums toward the event? also the references aren’t formatted properly, sorry!

Chapter 2. Unattractive Life (Fitness, Desirability, Lookisms)

“Second, things are so bad, so minimally imaginative for sexual relations, that people tend to do the thing they heard about doing just to keep things going, and if it means poisoning themselves and wearing out their bodies, or being over- or under- stimulated, even, they’ll do it. I do it. I make better decisions but not different kinds of decision.”1

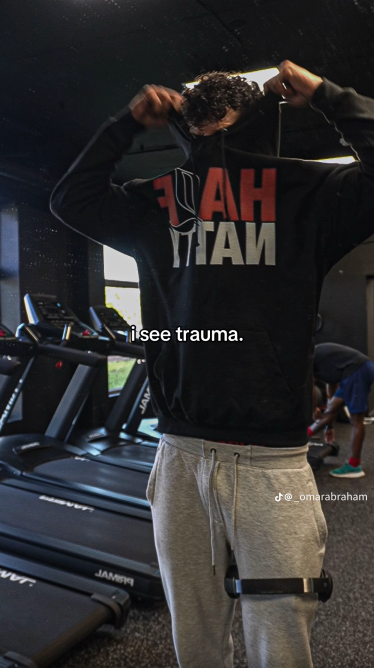

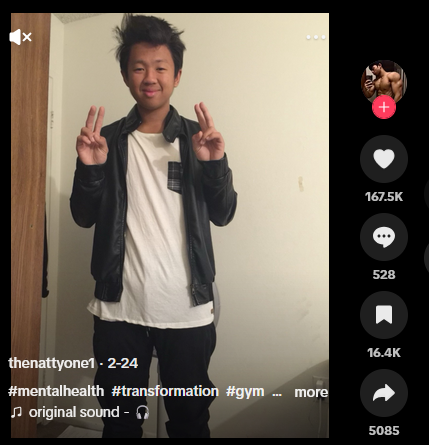

Figure 1.2

Unattractive life glosses a wider collective sense of exasperation and wonder that is a defining characteristic of contemporary dating and sexual culture. The case I seek to anatomize seeks to loosen the object – that is, unattractiveness – to stage the problem. For the more politically and critically minded, other explorations on the performance of attractiveness are available: Mimi Nguyen’s The Promise of Beauty explores the role of beauty as an aesthetico-political category that engenders spaces of fantasy, to navigate broken worlds and potentiate multiple felt possibilities;3 Ela Przybylo and Sara Rodrigues’ On the Politics of Ugliness4 provides contestation from the other end of the circuit, critiquing the deployment of ugliness as a historical process of racialization, colonization, ableism, heteronormativity, and fatphobia, ultimately divulging a “politics of ugliness” that operates at the level of relation – it is socially constituted – and biopolitics – it governs, manages, and marks certain populations for forms of life and/or death, each with distinct spatial and temporal substrates. In other words, ugliness impinges on certain bodies more intensely and intimately than certain others, with different resulting social and political arrangements.

But that much is significant to the language of ugliness or beauty. My emphasis on the phrase unattractive life points more towards the ordinary felt of attraction in the space of any typical relation. I am interested in the bodily, affective, and relational adjustments people make toward feeling pretty, ugly, or pretty ugly, as they continue to make sense of their attachments to the world, others, and their self-bodies. Hence the attempt here is situated in the dedramatization of (un)attractiveness in the space of romantic and sexual desire, to render the normativizing tendencies of what Berlant calls the “virtue squad” discursively out of their depth.5 Some samples of this virtue squad include incel subcultures,6 “black pill feminism”,7 and gender-critical feminism,8 all of which seek to reinstate a vision of sexual normativity different and promisingly better from current regimes of pleasure. Unattractive life thus vexes this sociopolitical question – of what we are doing with our bodies and our attractions – to offer a more tender vision than the virtue squad offers, to think more slowly what it means to labor in the reproduction of continued existence in a perceptibly difficult, hassling, and unsightly world.

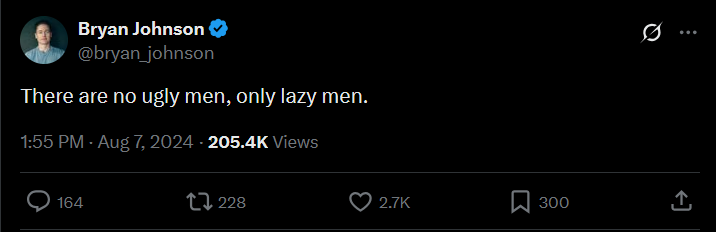

The offer here is more significant than it seems. The shift here tries to move away from conventions of dramatic encounters and structural determinism, taking as a starting point Berlant’s rearticulation of the sovereignty concept.9 Classical conceptions of sovereignty borrow from archaic traditions of state performativity and control, overinflating individual intentionality and consciousness in everyday decision-making and providing an alibi for the “justified moralizing” against poor (and impossible) choices as dramas of diseased will and morality. It casts inattentiveness and misdirected will as “irresponsibility, shallowness, resistance, refusal, or incapacity”, and habit and action as “…overmeaningful… differen[ce as] heroic placeholders for resistance… or a world-transformative desire”.10 In other words, this chapter opens the question on unattractiveness without capitulating to “the literalizing logic of visible effectuality, bourgeois dramatics, and lifelong accumulation or self-fashioning”,11 allowing for an alternative conversation on the obsessively painful and intense manners of self-sculpting that occur within the contemporary zone of sexual-dating cultures. In effect, it also contends the linkage between the socio-hierarchical, caste-like administration of sexual life to the “melodrama of the care of the monadic self,”12 not wholly divorced from the politics of ugliness but not entirely enveloped in it, either. This literalizing logic of sovereign choice over unattractiveness is best illustrated with Silicon Valley centimillionaire Bryan Johnson,13 most famous for his crusade against aging and the host of unattractive qualities that come along with it, including what he calls “penis health.”14 Selling longevity and staving off the unattractiveness of growing old, he proclaims: ugliness is an active choice one makes, even if sometimes it might cost a lot to not be old and ugly (about USD 2 million;15 Figure 2).

Figure 2.16

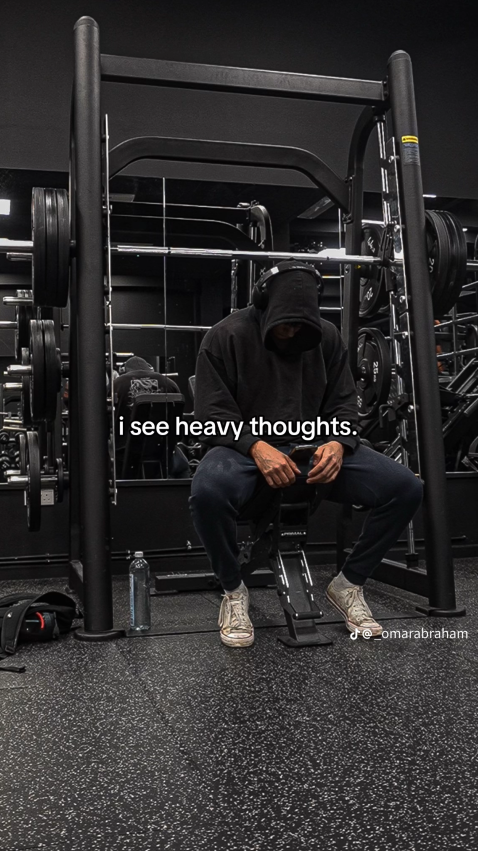

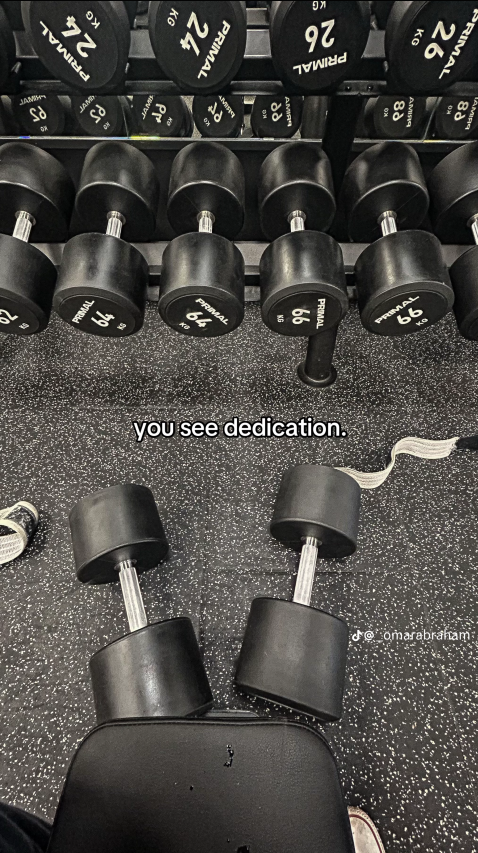

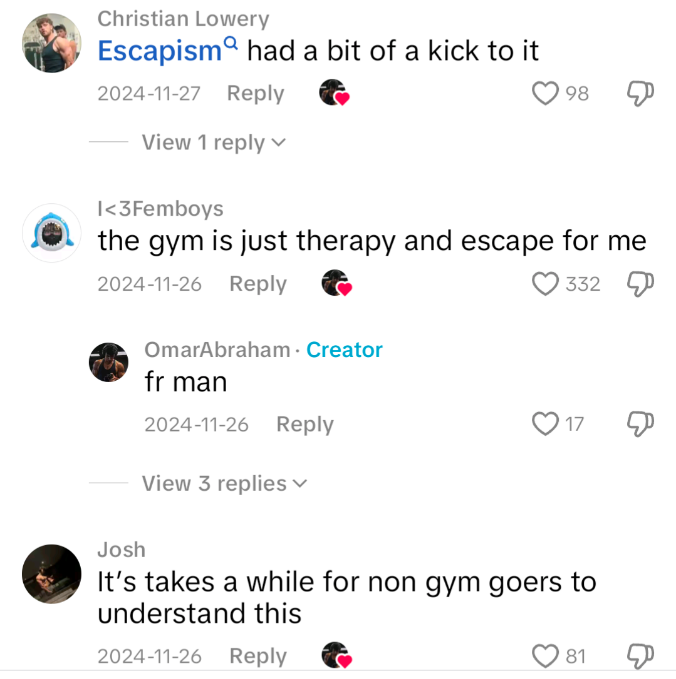

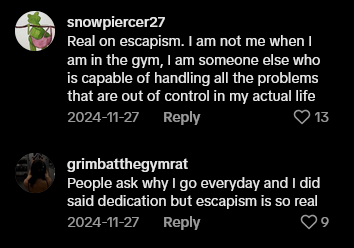

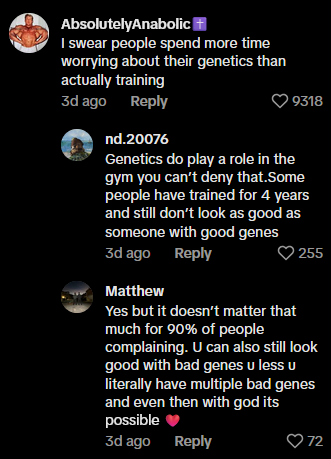

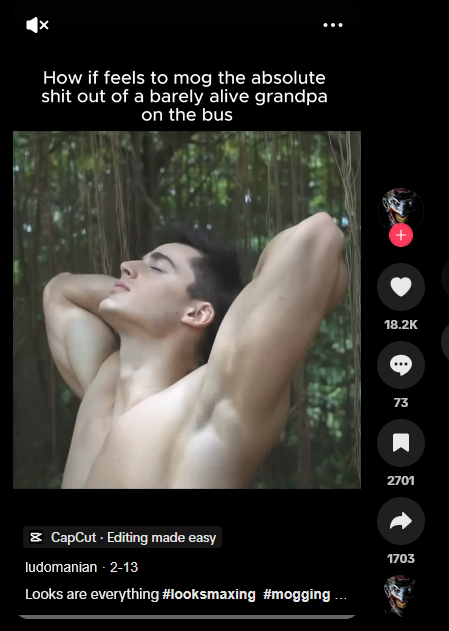

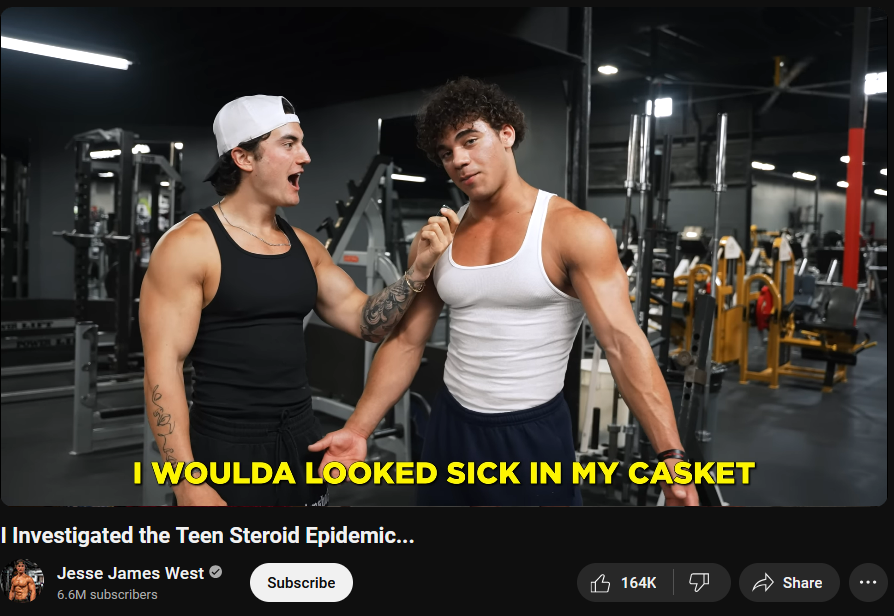

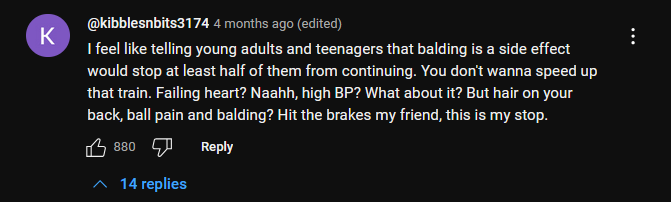

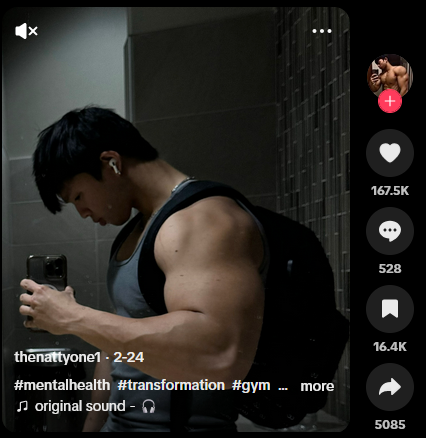

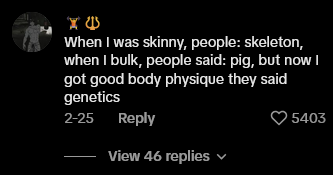

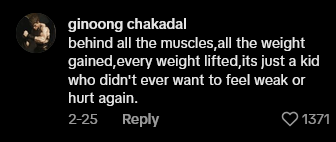

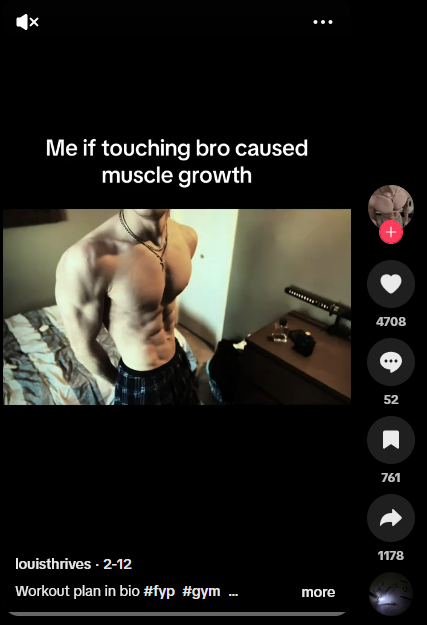

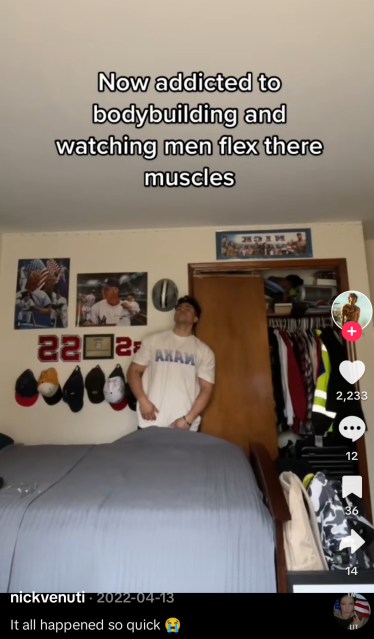

This chapter opens with visually striking proposition: that the achievement of masculine muscularity is neither motivated by promises of larger sexual apportionment (to “get more huzz”17) nor on the possibility of homosocial bonding (“to be with the bros”), but on a predominant and overwhelming sense of crisis ordinariness,18 one that is intensely personal and intimate at the same time that is it deeply impersonal and collectively shared. The TikTok in Figure 1 continues with two other complementary misconnections (Figure 3) – of escapism and mental baggage – that allegedly defines the muscularity of the fantasized image we typically see. I start with this TikTok because it offers this disconnect between the visibly spectacular and the implicit intractability of being spectacle; or in other words, it speaks besides the larger conversation of obsessive self-work in hopes of a good sexual/romantic life to propose that, perhaps, or after all, this obsession is borne from a position of impasse in a generalized every day. Such labor may permit the creation of erotic capital19 that leverages sexual desirability for (bio)power, but what interests me in these images is the inversion of that logic on its head – that the sight of a well-built body is, in fact, obscurantist politics for deeper misgivings, dissociative gestures, or just plain old trauma.20

Figure 3. 21

Figure 4. 22

Others elsewhere have suggested forms of episodic refreshment that, in reductive terms, give up on the idea of bodily longevity and social security in favor of coasting and floating by in our overwhelming present, including in eating and in sex.23 Here, the sculpting of an increasingly unattainable male sexual physique is another format of this coasting. “Looksmaxxing” renders out this term – popularized in early 2020s on TikTok and coined in the 2015s on incel forums24– into a culturally and memetically conceivable case. Looksmaxxing refers to:

“Any attempt at improving one’s appearance…. [involving] mild and well-known methods (such as getting a haircut, using minoxidil and grooming eyebrows) to more invasive techniques such as plastic surgery and using anabolic steroids.”25

More precisely, it is a self-obsession with the quantification of physical and sexual attributes in the pursuit of optimizing, or “maxing out”, one’s attractiveness. It qualifies as the freshest case of structural intractability within the domain of everyday social existence, one that has been rendered into multiple other cases, including heteropessimism26 and crises of health-management (orthorexia, bigorexia, muscle dysmorphia)27, arguably as a logical end to the administration of sexual politics tenderized by digital dating cultures. This chapter will begin by unfolding this case of looksmaxxing, pairing social media, comments, and other content to articulate this problem of unattractive life as predicaments to contemporary sexual-dating cultures. This, obviously, engenders a laundry list of strong and florid analytical scales – i.e., the westernization and white-empowerment of attractiveness; its pairings with social austerity and social media’s hyper-individualized algorithmic spaces; nutritional, physical, economic, and sociopolitical impairments; racial and sexual fetishization; mano-spheric sexualities and sexual hierarchies; and so on – which I cannot possibly hope to reduce in this chapter. I recast this situation outside of the fantasies of sovereignty and the reproduction of an attractive life to think about how exercise loses its tone of attractiveness and leans towards the re-habituation of self-labor in the pacing of everyday unattractive life.

The case here tries to unpack questions of agency, action, and self-labor and eschew clarity in favor of dissociative impulses that try to dissuade any full and measured grasp of the situation. The effort thus will look tattered and piecemeal; but that is by design, particularly as it represents the sort of activity that one might engage as an online “bystander” within discourses of unattractive life. It tries to divulge the mediation of sovereignty in looking good/bad via the digitalization of masculinized sexualities, or muscular hype, or “looksmaxxing” advice, without feeding back into moralizing or adjudicatory processes that make something look bigger than it might truly be.

The Case of Looksmaxxing

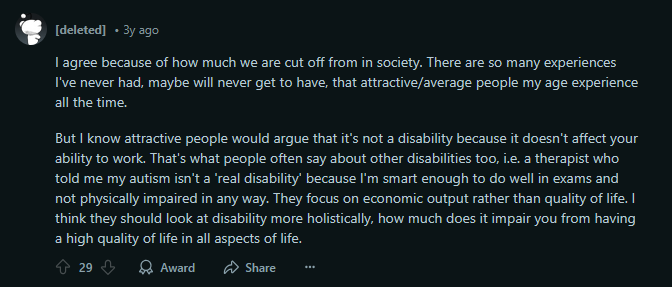

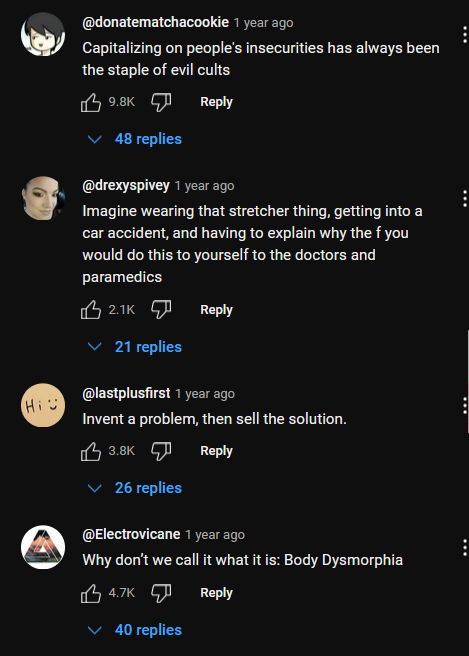

Looksmaxxing might translate effectually as this countervailing tendency against un-health and unattractiveness, as an exercise of morally correct will and active self-improvement like good and happy late liberal subjects should. Nonetheless as the opening visual shows (however unconvincingly), this interpretation might be misguided in its focus; a sharper critique of this exercise can be articulated in the public discussion of looksmaxxing and its various trends that turn attractiveness into a health-pedagogy, a value-creating project that may or may not administer effective treatments to ill will and unattractive life. The post below speaks to this treatment as an attempt to explain unattractiveness as disability (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Eerily echoing David Harvey’s polemical observation in Spaces of Hope; in defining sickness and disability as the inability to work,28 it serves as one part of this response to unattractive life. Certain individuals are “too far gone” to be able to be saved, to an extent where one can consider them having a functional disability or impairment in everyday existence.

Figure 6.29

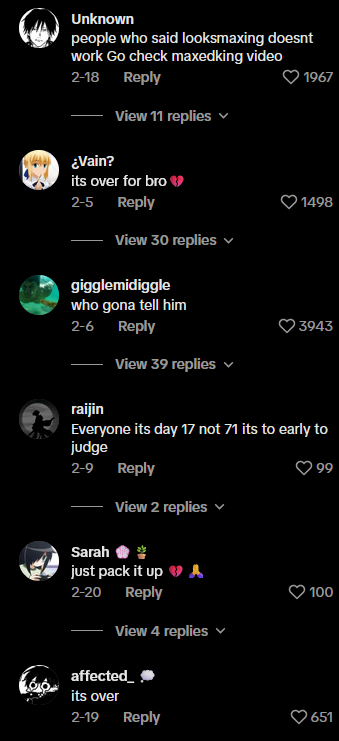

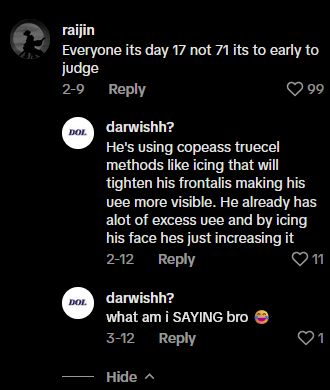

Unsurprisingly, such castings figure on bodies more peripheral to the central vision of white-western masculinity – above depicts a looksmaxxing method of face icing30 practiced by an Indonesian content creator with comments already calling it in for the looksmaxxer-to-be (Figure 6).31 The language deployed to articulate these intricacies is overmedicalized in an attempt to legitimate scientific and empirical credence in these methods, leading to advisories full of verbose medicalized jargon:

Figure 7.32

In other words, face icing only exaggerates this individual’s upper eyelid exposure (UEE) and serves only to give them baseless hope (“cope”) in any actual improvement in his objectively poor physical facial features (Figure 8).

Figure 8.33

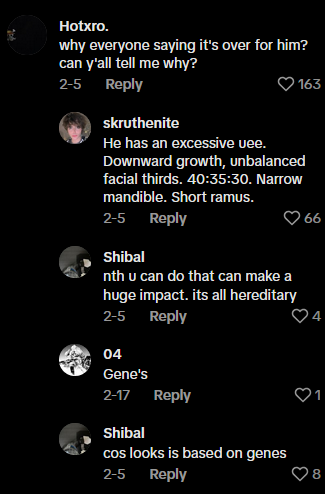

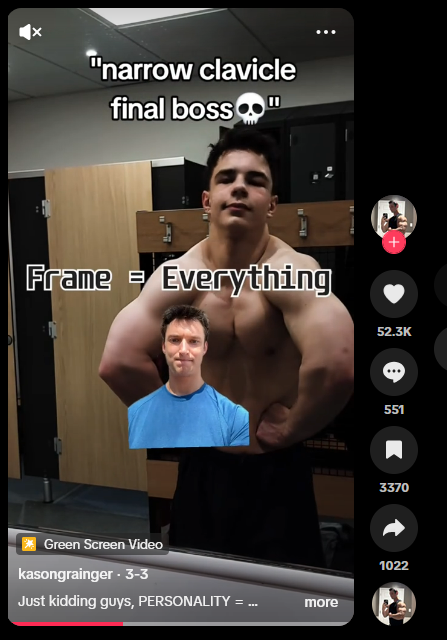

This sort of shot-calling – or shutting down – of the project typically projects a fatal certainty in biological immutability and genetic “destinies” through specific medicalized terminologies. One example is the clavicle, a shoulder bone that determines the width of one’s shoulders and upper body, where a shorter one is less preferred. Clavicular size in this instance is seen as immutably true, determining the actual attractiveness of anyone’s attempt to looksmax.

Figure 9.34

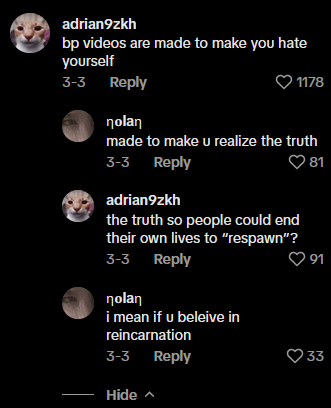

The appearance of these discourses takes the shape of the “black pill/bp”, or the supposed objective realization of the “truth” of impossibility in recovering from unattractive life.35 The fatalism of the black pill in this situation is not quite the same as typically deployed in the manosphere, however – it appears to be more skeptically received in light of the possibility for anyone to improve their looks, however marginally so.

Figure 10.36

Commenters here front human capacity to look better through sheer hard work and discipline to cushion against this despairing impossibility. This tension between genetic or biologized immutability and disciplined self-labor is one of many contestations centered around looksmaxxing and unattractive life writ large; whether methods of looksmaxxing are mere “coping” mechanisms to avoid acknowledgement of the harsh reality of ugliness or are actual proven interventions that “fix” unattractiveness ground this tension, which is why the overdetermination of medicalized terminologies operate at such a high level within these spaces. Medicine and science can emprirically and provably demonstrate the efficacy of any method and the ground truth of anyone’s appearance, even as science itself can be tested, hypothesized, and falsified.

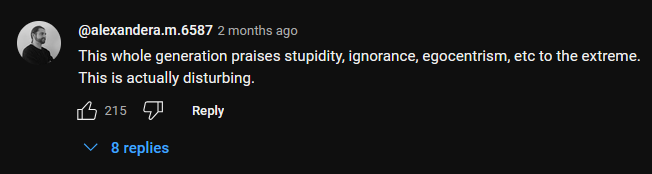

As mainstream media struggles to grapple with this case, of which I have so far only provided a small focused cluster of factors, headlines pulsate with an intangible worry for what the trend marks – is it political polarization? Toxic masculinity? Gendered violence? The male gaze, turned inward? The “new Red Scare”?37 Clearly there is something wrong, primarily with our young men, but it is hard to tell what’s going on. Nonetheless various actors in the social media sphere recapture the phenomenon to redirect individual agency toward other forms, “amplifying moral and political urgencies in any and every possible register”.38

\

\Figure 11.39

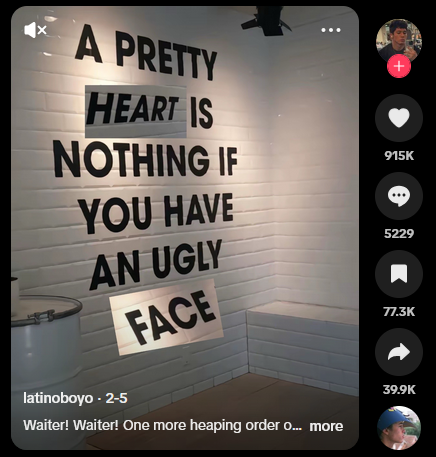

Looksmaxxing operates as one long diffuse arm of the normativizing effects of the squeezing of bodily desirability within the space of a more perceptibly difficult “aesthetic” life. Unattractive life haunts the physical embodiment of every “body”, as looksmaxxing proposes uneven casting into sexual-visual-aesthetic regimes that glorify and reify biopolitical attributes predominant in digital-global sexual cultures. Here adjustment is framed by the rhetorical purchase of the sovereignty concept, either as an insatiable compulsion to look better, to get bigger; or as a disease of the will, as slave to the male gaze. Extensions of the problem of being in/of unattractive life are less assured by outsized dramatics of agency that paper over the thinness of zoning within the relational everyday and in the pacing of everyday slow death.40 In other words, to say that one must choose to not feel ugly, coded in a different language of “choosing yourself”, is unconvincing at best and debilitating at worst, especially for those inevitably cast into the project of unattractive life. Conversions of sovereign choice away from one type of obsessive self-work to another (from looksmaxxing to “self-help”) do little to challenge the overall problematic. On the other hand, the achievement (or failure) of spectacular muscularity need not be celebrated as a triumph over obstacles to physical or mental flourishing or as a fundamental brokeness overdetermined by social structures of capital, exchange, and sociality, however much this elaboration of habit/action and structure/cause might affectively incite feelings of (un)fulfilled embodiment.

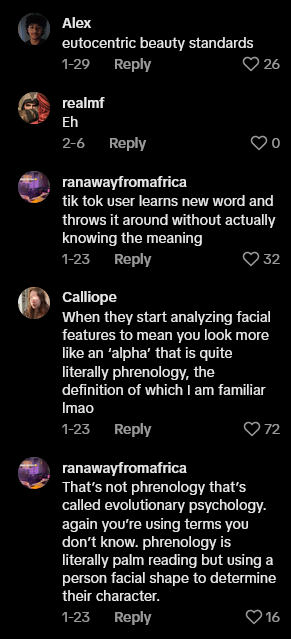

This genealogy of unattractive life nonetheless finds itself straddling a familiar accusation of western/eurocentricity and white exceptionalism, whether it be levied as a problematic impersonal assertion or “evolutionary psychology”. It confuses the feeling of desire for inalienable facts of nature, wanting to be white/right, whilst prescribing no less than full intentionality in the very expression or experience of that desire.

Figure 12.41

This symptomatic of unattractive life characterizes, again unsurprisingly, bodily propensities of certain populations more than others; working class, subproletarian, persons of color. This tale of literal white-washing is retold as methods of skin lightening and skin bleaching throughout much of the rest of the non-white world, acting as yet another crisis-scandal health-management of unattractive life that models public health awareness as comorbid with the biopolitics of race and gender.42 It is no surprise that looksmaxxers are regularly accused of upholding a “white” or “eurocentric” ideal of beauty, many of whom argue that such a tendency toward sameness or similitude among their sort of ethnically diverse cast (mostly Middle Eastern, European, American43) is just a realization of this latent genetic predisposition – everyone is “biologically wired” to prefer certain physical traits over others, coincident with attributes most exclusive to white or european features.

It is insufficient to say that these people have an illness of desire that requires an exhortation of such to move towards a more politically labile fantasy, just as it is insufficient to model other kinds of embodiment (“dark is beautiful”) that may or may not look concrete and tenable as alternatives to inhabit. Be it with short men or dark women, the work within unattractive life embroils one in stringent discourses of sovereign control and choice that provide no exit from one’s own embodiment and physicality (Figure 13). Looksmaxxing offers this psychosocial defeat in beginning the process of hammering, mewing, and sculpting your body toward this model of (white) attractiveness, eschewing the more impossible work of examining our desires, where they come from, and how to really “change” them, if even. It marks an initial departure from sovereignty whilst remaining in a phantasm of it, as the impossible, incredulous methods of looksmaxxing look increasingly like dissociative, laborious acts that try to shed the weight of being in life, unattractive life.

Figure 13.44

This disarticulation of agentic action also cannot be phrased in a way that reinscribes structural determinism – retreating back to medicalized understandings, muscle dysmorphia or “bigorexia”, a well-defined psychiatric disorder with schedules in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-V) and characterizes a pathological obsession with one’s musculature being too small or inadequate, can indeed be a “moral issue” stemming as a “rational response to an absurd situation,”45 but what qualifies it as moral or rational? Not every action is taken in full response to the absurdity of any situation; it is impossible to account fully for the ways in which world-making efforts are desired, understood, or even felt as something more than a passing hand wave, just like how no critique has fully accounted for every detail in a novel.

At the other end of the vibrant circuit is the looksmaxxer, one that can viably take charge of their sociosexual success even in an uneven playing field, advised to and lectured at to go on a high-testosterone diet, or to exercise (of course), or to hop on tren,46 or to gain mass, or to lean bulk, or to get their heart broken, or to fix their financial health, or to stop masturbating, and so on. Here I am also gesturing toward the varities of structural and interpersonal conditions that require recalculation in the etiology of looksmaxxing, of which it is likely impossible to characterize in full. In this scene of endemic diminishment, overinvestment in structural adjustments look more heroic than not (virtuosity in “mogging”47 the rest of the fat and ugly); more absurd that not (intractability in flesh-refinement and limits of genetic/biological dispositions); more real and material than not (physical appearance > personality; physical appearace = personality; Figure 14).

Figure 14.48

“Escapism” as Interruptive Agency

So far, I have attempted to examine the dispersal of causal mechanisms that underlie the case of looksmaxxing. Here I want to cleave the image of unattractive life from the physical and psychosocial labor that underwrites the practice of maxxing one’s looks. Indeed, this excessive or absurd obsession is often “a fitting response” to the current absurd situation, but calling it rational mischaracterizes the extent to which episodic interruptions to the building of an attractive life act to disrupt the tinniness of laboring and self-obsession. It misses the ways in which looksmaxxing practices may be better described as dissociative or coasting, providing leeway for the unattractive to momentarily release the social and sexual demands of the self-other. The loudness of the discourse of looksmaxxing might make such an assertion look ludicrous, especially as it espouses its central tenet as both rational (admit to your biological destiny) and agential (only consistent effort and discipline in habit formation will save you). But therein lies the kernel – whilst the performance of these habits are necessarily dramatic (as videos, social media content), consumption from this perspective involves a form of controllable, reliable labor that in itself acts as a dissociative impulse toward minor pleasures.49 Any result borne of these repetitious procedures are merely recollections of these dissipatory scenes of satisfaction, which is typically hard to reliably measure anyway (recall the compensatory overprecise medical science of looksmaxxing).50

The suggestion here is thus no longer concerned with the amending of structural contingency or individual agency, but rather is interested in thinking about a different inhabitation of agency and action, a mode of expending labor and time that may or may not be about value-creation in the throes of erotic capital and sexual-visual cultures, and more about how looksmaxxing embodies the pleasure of self-abeyance, of “floating sideways”, neither “self-negation [n]or self-extension”.51 One might be tempted to view this new format of being in the world as resistance to the vampirism of value maximization that saturates the contemporary, but that overdescribes the effectual case of such restlessness. The question, thrown into relief, is the re-conceptualization of life unto death, where:

“…eating adds up to something, many things: maybe the good life, but usually a sense of well-being that spreads out for a moment, not a projection toward a future. Paradoxically, of course, at least during this phase of capital, there is less of a future when one eats without an orientation toward it.”52

Here I offer another conjoined scene of this frentic fraying of unattractive life and the varities of attempts to hammer out, quite literally, episodic refreshment strictly discontinuous with larger life-building work, or inchoate with building something that is meant to last. Uses and abuses of anabolic steroids, typically mobilized as hot weapons for the moral tragedy of this shocking epidemic of unattractive life, pan out as agentic failures of all kinds, ignorant of the endemic environment of its emergence.

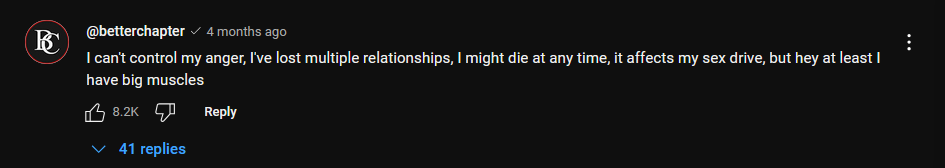

Figure 15.53

Akin to the overt moralization of this failure of will and morality with obesity yet distinct in its articulation, the “monstrification” of self-labor54 serves as fertile ground for explicit shaming of these bodies. Why would anyone poison (eat, work, inject) themselves to death? The ersatz response to this is simple and presumably superficial: I’d rather die young and attractive than old, ugly, and infirm. This damning assertion, beyond just an indictment of the loss of life-affirming potentiality in the scene of everyday living, is also indicative of this askew optimism to look better, to push past unattractive life into attractiveness even if it spells death or disability, even as unattractive life is seen as the more debilitating disability to have. No less is academic literature highly critical of the physical and psychosocial implications of anabolic steroid use, as folk ethnopharmacology tries to remediate the compulsion to look bigger and better with the liberal sentiment to do less harm (harm reduction).55

Figure 16.56

Nonetheless in this span of dithering time where unattractive life haunts the visible horizon of possibility, the literal exertion of muscular labor serves as a reliable and suspended reprieve in the project of watching some body grow, constituting an actual body that approximates a sovereign, powerful subject. Anabolic steroids accelerate this cycle (not without its inconveniences57), shifting the gear of this reprieve in ways that enact more intensely bodily engagements with unattractive life. This shortening of the circuit is no stranger to the speed-up of work in capitalist time, but also familiar to the pacing of everyday organized by gym visits, sets, repetitions, specific muscular groups, and nutritional cataloguing, as “lifelogging” – the tracking of each and every instance of life as event, including caloric intake, exercise repetitions, sleep, drug consumption, breathing patterns, and so on.58 Knowledge of the supposed harms of these practices, including this drive for hypermuscularity, do little to millitate these men against unattractive life; ethnographies of bodybuilding cultures suggest that this sort of self-labor is both patterned and predictable, if not unhealthy and consistent.59

In the above video by @Jesse James West, the supposed “teens” all articulate specific aspects of steroid use that perceptibly contradict this aim to “look better” – undesirable hair growth, premature balding, acne, and “ball cramps” plague their bodies, whilst comments jostle on how these physical side effects should deter others from doing the same thing. Building a visibly muscular body, then, is the key for content creation and inauguration into the throes of the “bodybuilding”/looksmaxxing community; nevertheless for the views and gains, even if it means “poisoning themselves and wearing out their bodies,” 60 but not in ways that remain legible to frameworks of agency and personal choice – it just feels good to flex and get compliments for it.

Figure 17.61

This scene animates what’s vibrant about the space of attrition – the activity of building mass is itself impassive, no longer dedicated towards affirming health and toward a model of un-health, as many might now argue. One cannot understate the amount of effort that goes into cataloguing every instance of every day as a specific event curated for attractiveness-building – it almost dupes itself by mimicking practices of life-building.

Figure 18.62

This gestural or figurative movement of mimicry, though discontinuous with actual life-affirming projects, is itself continuous with the labor of dissociation complete “with a saturating image” of itself,63 expressed most evidently in this self-interested – or self-obsessed, depending on the how saturated the psychic scene is in disaster – practice of sharing images of muscularity. Jamie Hakim’s work on this homosocial phenomenon draws out this dramatic contradiction of joy and emptiness,64 but I argue it appears better pronounced in the language of the interesting, a standard of minimal indeterminacy as an aesthetic genre65 that more fittingly loosens the spectacularity borne by the bulging muscles and “remain[ing] in a drama we know.”66 For most, the unwilling inaguration into unattractive life – as a pathetic, ugly, weak, dissimilar loser – is that very same drama that is hooked into this flat, detached, “cool” expressivity augmented by muscular, clavicular, or facial spectacle (Figure 19).

Figure 19.67

Coda: Sameness and Fading

Unattractive life straddles a moment in present history where paradiagmatic encounters with meeting and getting with others couples an intensified practice of self-labor and the curation of attractively benign pleasures. It does not simply encompass the faceless torso gridded textures of grindr,68 nor the promises of swiping stacks of profiles optimized for the greatest (not) amount of engagement,69 though in both of these scenes the motivation to “be yourself” squares against the difficulty of “being as yourself”. Nonetheless the opening of this conceptual offer gives shape to our current biopolitical phase and the uneveness of such. Here I want to shift gears again, to think about this “enormous effort… [to] succeed in looking like others”70 and its potentiality in an overwhelming present.

Figure 20. Between a physique check & a grindr grid.71

I do not take to mean this profound sameness in the same way that Bobby Benedicto yearns as gay twinning and the over-annihilation of this sameness in an racialized “Other”, although that is more likely the case for certain bodies who share this burden of “being (mis)recognized as nothing”. 72 The proposal for muscularity fortunately or unfortunately shapes into the same space, shape, form, of chiseled torsos and bulging pectorals; there is almost something homoerotic about similtude that many online bodybuilders like to reference as the overwhelming influx of male engagement on both their content and other’s (Figure 21).

Figure 21.73

But even in this space of minimal imaginativeness, this desirous viewing and inevitable sameness lapses into the dissipation of the bodily subject, a softer, slower kind of social attrition:

“Why? Because it’s such a self-obsession and doesn’t equate to anything really for the future, for building yourself as a person, building your body.”74

“There is something harsh and funny about the repetitions of power,”75 herein as actual physical power, deployed in similitude with a homoerotic suggestion in tow (Figure 20). There is, indeed, something funny about the exertion of muscular power in suggestion of masculine achievement and the pairing of homoeroticism as declarative assurance in that very same performance of masculinity. Whereas the harshness floats around, somewhere discernible between the peaks and folds, humor about the absurdity of the entire performance (of masculinity, of muscularity) acts both as realism about what works and what doesn’t, and what to do next, albeit only tentatively.

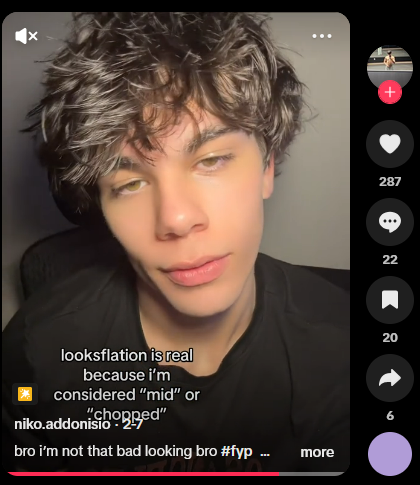

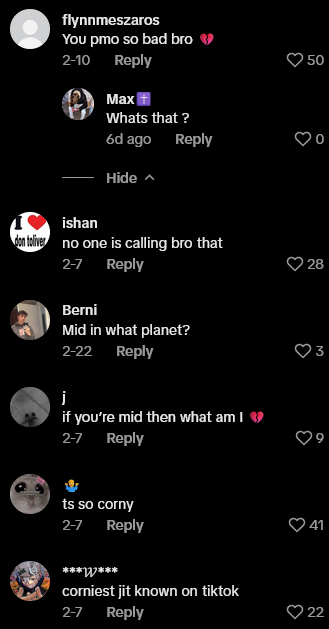

Figure 22.76

The corniness of calling out a “looks-inflation” is this absurd yet realistic logic – one can even levy accusations of being too “online”, too surrounded by figures of attractive life, maybe even too self-absorbed to realize how good they have it. But the space of failure is neither even or homogenous; the attempts to hammer out objects and worlds worth living in and living with have no equivalency beyond themselves; they are things worthy of caring for. In this narrowing of sexual, relational, and social fantasy, reproduction of a reliable, disciplined everyday necessitates regulatory sustenance in habits, actions, and performances that exerts “lateral agency”77 in counterabsorptive practices like humor, homosociality, sex, “spacing out” or scrolling out, or food that is overthought.

https://supervalentthought.wordpress.com/2012/05/16/for-example/#more-635 ↩︎

Nguyen, Mimi Thi. The Promise of Beauty. Duke University Press, 2024, 30. ↩︎

https://link.springer.com/book/10.1007/978-3-319-76783-3 whatever cite this later ↩︎

Sex without optimism, 14 ↩︎

https://www.lrb.co.uk/the-paper/v40/n06/amia-srinivasan/does-anyone-have-the-right-to-sex ↩︎

https://capaciousjournal.com/article/heteropessimism-and-the-pleasure-of-saying-no/#_edn1 ↩︎

https://www.google.com/books/edition/Gender_Critical_Feminism/VL9qEAAAQBAJ?hl=en&gbpv=0 ↩︎

Berlant, 96 (cruel optimism) ↩︎

Berlant, 99 ↩︎

Berlant, 99 ↩︎

Berlant, 99 ↩︎

https://www.nytimes.com/2024/01/12/business/bryan-johnson-longevity-blueprint.html ↩︎

https://blueprint.bryanjohnson.com/blogs/news/how-i-m-de-aging-my-penis ↩︎

https://www.nytimes.com/2024/01/12/business/bryan-johnson-longevity-blueprint.html ↩︎

https://x.com/bryan_johnson/status/1821243852411564330?lang=bg ↩︎

Slang for “hoes”, typically as sexual innuendo. ↩︎

https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/09589236.2016.1217771#d1e313 ↩︎

Hakim, 234 ↩︎

Comments on https://vt.tiktok.com/ZSjqetunj/ ↩︎

Berlant, CO, slow death, 119 ↩︎

Orthorexia refers a pathological obsession with eating healthy; see https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.2147/NDT.S61665. Bigorexia and muscle dysmorphia overlap and typically refers to a pathological obsession with feeling inadequately muscular or small; see https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1002/erv.897 ↩︎

Cite spaces of hope here ↩︎

https://www.tiktok.com/@iam.willcar7/video/7467562103633644806?_r=1&_t=ZS-8usvNNDdiQK ↩︎

As a method to “chisel” the face that is reportedly not as impactful as other practitioners purport. See https://looksmax.org/threads/icing-your-face-in-the-morning-is-the-biggest-looksmax-you-can-do.699906/ ↩︎

Identifiable from the other TikToks on the user’s page. ↩︎

https://www.tiktok.com/@iam.willcar7/video/7467562103633644806?_r=1&_t=ZS-8usvNNDdiQK ↩︎

https://www.tiktok.com/@iam.willcar7/video/7467562103633644806?_r=1&_t=ZS-8usvNNDdiQK. As demonstration of the specificity of the medicalized language: “downward growth” refers to the downward shifting of the lower part of an individual’s face that leads to less defined jawlines and a flatter sidewards facial appearance; excessive “upper eyelid exposure” refers to the thickness of the individual’s upper eyelid, where thinner upper eyelids are preferred to give the eyes a sharper, more “predator” like look; “unbalanced facial thirds” refers to the distribution of particular facial sections (nasal, forehead, lips); “40:35:30” may refer to the unbalanced facial ratios of these different sections of the individual; “Narrow mandible” refers to a smaller lower jaw, leading to a smaller chin and less vivid jawlines; “Short ramus” refers to the section of the lower jaw that determines the side length of the jawline. ↩︎

https://www.tiktok.com/@kuinonefein/video/7482930972195917072?_r=1&_t=ZS-8usuoIOSlta, https://www.tiktok.com/@kasongrainger/video/7477679715482979615?_r=1&_t=ZS-8usvInKCqAB ↩︎

https://www.tiktok.com/@kuinonefein/video/7482930972195917072?_r=1&_t=ZS-8usuoIOSlta, https://www.tiktok.com/@kasongrainger/video/7477679715482979615?_r=1&_t=ZS-8usvInKCqAB ↩︎

https://www.theguardian.com/lifeandstyle/2024/feb/15/from-bone-smashing-to-chin-extensions-how-looksmaxxing-is-reshaping-young-mens-faces; https://www.bbc.com/culture/article/20240326-inside-looksmaxxing-the-extreme-cosmetic-social-media-trend; https://www.nytimes.com/2023/11/06/style/looksmaxxing-tik-tok-dillon-latham.html; https://theconversation.com/looksmaxxing-is-the-disturbing-tiktok-trend-turning-young-men-into-incels-221724; https://www.menshealth.com/grooming/a63149374/looksmaxxing-auramaxxing-scentmaxxing-trend/ ↩︎

Berlant, 104 ↩︎

Berlant, 105 ↩︎

https://www.tiktok.com/@josh_nabbie/video/7455111967146003742?_r=1&_t=ZS-8uswA0ii5H0 ↩︎

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2352647520301416 ↩︎

https://www.nytimes.com/2023/11/06/style/looksmaxxing-tik-tok-dillon-latham.html ↩︎

https://www.reddit.com/r/shortguys/comments/15dbqqi/meta_post_antiheightism_gaslights_and_the/?utm_name=androidcss ↩︎

https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/full/10.1177/13634593221093494 ↩︎

Short for trenbolone, typically administered in its acetate form as a synthetic anabolic-androgenic steroid that promotes androgenic effects, most notably muscular hypertrophy. There is a whole family of performance-enhancement drugs that circulate within the grey market of steroid use – see https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/16066359.2024.2352092#abstract, https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2211266924000288 ↩︎

Refers to “…a verbification and apheresis of the acronym AMOG for alpha male of the group; is the act of dominating another person”, typically employed as a show of superiority in appearance or capacity over another. See https://incels.wiki/w/Mogging ↩︎

https://www.tiktok.com/@stevocircle/video/7483323059483528491?_r=1&_t=ZS-8usuqPx4H5e; “gaf” = give a fuck, “irl” = in real life.; https://vt.tiktok.com/ZSr1AE4Dn/; https://vt.tiktok.com/ZSr1DMPSU/ ↩︎

Berlant, 115 ↩︎

Which is also related to, but not similar with, conceptions of “science-based” lifting or “broscience”; see https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2211266924000288 ↩︎

Berlant, 116 ↩︎

Berlant, 117 ↩︎

https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/full/10.1177/1357034X241293037 ↩︎

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2211266924000288 ↩︎

https://journals.lww.com/acsm-csmr/fulltext/2018/07000/Physical_Effects_of_Anabolic_androgenic_Steroids.5.aspx https://www.mdpi.com/2227-9032/9/1/97 ↩︎

Puar, in cost of getting better, 4. And https://www.nowpublishers.com/article/Details/INR-033 ↩︎

https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/full/10.1177/13634593221093494, https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0955395920304254, https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/09589236.2016.1217771#abstract ↩︎

https://supervalentthought.wordpress.com/2012/05/16/for-example/#more-635 ↩︎

Berlant, inconvenience 120 ↩︎

https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/09589236.2016.1217771#d1e313 ↩︎

Ngai, merely interesting, 790 ↩︎

Berlant, inconvenience 120 ↩︎

https://nymag.com/article/2016/06/growing-up-grindr-a-millennial-grapples-with-the-hook-up-app.html ↩︎

https://www.theatlantic.com/technology/archive/2024/04/dating-apps-are-starting-crack/678022/ ↩︎

Hardwick, sleepless nights, idk what page ↩︎

https://vt.tiktok.com/ZSr1AgYpQ/, https://nymag.com/article/2016/06/growing-up-grindr-a-millennial-grapples-with-the-hook-up-app.html ↩︎

https://read.dukeupress.edu/glq/article/25/2/273/138545/AGENTS-AND-OBJECTS-OF-DEATHGay-Murder-Boyfriend p286 ↩︎

https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/09589236.2016.1217771#d1e313 ↩︎

Berlant, inconvenience, 147 ↩︎

https://www.tiktok.com/@niko.addonisio/video/7468565018439585054?_r=1&_t=ZS-8v1K3dfpOaY; “chopped” = ugly looking; “pmo” = piss me off; “mid” refers to an aesthetic and value judgment of mediocrity, “middling”; “ts” = this or this shit, depending on format and tone; “jit” = young thug, more emphasis on downward age difference ↩︎

Berlant, slow death 119 ↩︎